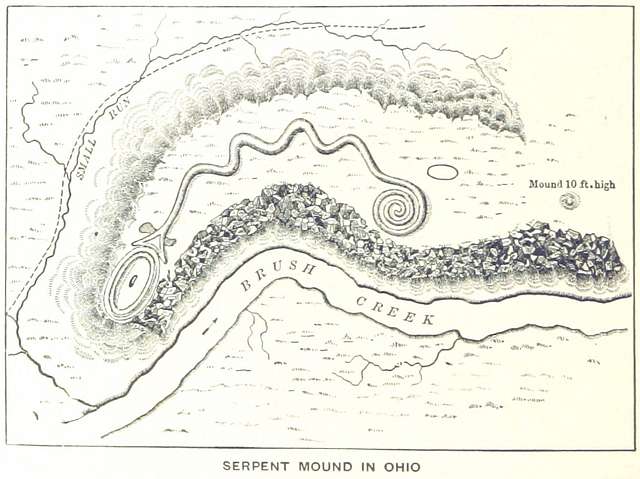

Between roughly A.D. 700 and 1200, earthen mounds in the shapes of animals were built by Woodland peoples along the Mississippi and Ohio rivers and near Lake Michigan. The greatest concentration of animal effigy mounds (numbering over 800) is found in southern Wisconsin, and the most widely known effigy mound, Serpent Mound, is in southern Ohio. Some early accounts speculated that the effigy mounds represented “spirit animals.” Modern-day archeologists now generally regard the animal effigy mounds as “clan symbols” and social gathering sites of the different tribes that inhabited the area. In June 2001, I visited Serpent Mound in Peebles, Ohio, which is a large effigy mound in the shape of a snake with a coiled tail, a winding mid-section, and what many describe as an egg in its mouth.

I first walked down along the path that runs beside the Serpent Mound towards the head of the great snake. Numerous signs are posted along the way warning the visitor not to climb on the mound. But my enthusiasm got the better of me, and with no one watching, I climbed onto the egg in the serpent’s mouth and started walking along the top of the mound from head to tail. About halfway down the length of the serpent, I felt the undulations of a giant snake moving under my feet. The mound was alive! The spirit felt joyful and happy. My experience of the serpentine energy was cut short, however, when just as I neared the spiral tail, the manager of the state memorial caught me, and told me to get off the mound. As I was driving away, I realized that the pain in my gallbladder, which had troubled me for some weeks, was gone and I felt great! Could it be true? Were there really spirits in the mounds? I had to visit more mounds to find out.

My next trip was to the Effigy Mounds National Monument near Marquette, Iowa, where 191 prehistoric Indian mounds are preserved. The largest group of effigy mounds in the park, called the Marching Bear Group, is found along the South Unit Trail, and is so named for its ten bear mounds all “marching” in a line.

On the day I visited, hiking on the South Unit Trail was difficult due to dense fog, intense mosquito activity, and lightning and thunder along the top of an open prairie ridge. I was determined, however, to visit at least one mound before descending to safety. As I stepped onto a bear mound in the Marching Bear Group, I felt a shudder under my feet, like I had accidentally stepped on a sleeping dog. The mounds here were clear of trees, but overgrown with grasses and weeds. They looked unloved and neglected, which was so very different from the much visited and beautifully maintained Serpent Mound. Was the spirit in this bear mound asleep due to a lack of human attention? This visit confirmed for me that it is possible to experience the spirits of the effigy mounds at other sites, not just at Serpent Mound.

I searched books and articles looking for information about the effigy mounds. In one article about the effigy mounds located on the grounds of Mendota Mental Health Clinic in Madison, Wisconsin, Dr. Gary Maier described how the spirits of the mounds have “visited” patients and staff members in their dreams. In one young patient’s dream, an Eagle Spirit opened its wings and made a safe place for the child, protecting the child from a nightmare monster. Interestingly, the children’s unit at Mendota is located just 20 to 50 feet away from the largest bird effigy mound still in existence.

Native Americans were, no doubt, familiar with the spirits of the effigy mounds. According to Ross Hamilton, author of The Mystery of the Serpent Mound, “the serpentine effigy was created as an active, fully functioning Manitou“. Graham Hancock in his book, America Before, notes that the Native American notion of a Manitou can be an individual spiritual entity, a Great Spirit, as well as an unseen force that animates all life.

The science of the mounds? The mounds are not just a simple heaping of dirt – they have an underlying structure. Serpent Mound has a layer of clay and ash at the base, then a layer of rounded stones, more clay, followed by dirt. Here is the diagram from the museum at the site:

This construction may give the mounds unique physical properties. For example, in landscape magnetic field surveys at both effigy and ceremonial mounds, the mounds display a greater magnetic field strength than adjacent soils. In 2012, Dr. Jarrod Burks, from Ohio Valley Archaeology, Inc., conducted a magnetic gradient survey at Serpent Mound. In this gradiometer map from his study, the structures in black show the highest magnetic field intensity.

We have seen in previous blogs that energy healing is associated with an increase in magnetic field strength during healing sessions. Thus, the higher magnetic field strength on the mounds could lead to healing (as for example, in my case with gallbladder pain). Furthermore, if we consider the spirits of the effigy mounds to be composed of plasma, then the magnetic field of the mound may act as a “cage” containing the spirit.

Unlike conical mounds, effigy mounds rarely contain human burials; instead, they often contain a stone altar and burnt charcoal located in the “heart” region of the mound, suggesting some sort of ceremonial use.

What sort of ceremony? One possibility is that the Woodland Indians practiced a form of animism. In this type of religion, either the animal spirits were experienced at these sacred sites and then a “home” or mound was built for them, or a home was built for the spirits who were “invited” to dwell in the mound. Either way, the mounds would be understood as homes for the spirits, and the ceremonies as a means of “connecting” with the spirits. Incredibly, at some of the mounds, the spirits are still present, despite hundreds of years of neglect, and are still able to provide spiritual nourishment and healing for their human visitors.

References:

Moga, Margaret (2003) Spirits of the effigy mounds. American Society of Dowsers Digest, 43(1, Winter): 29-30.